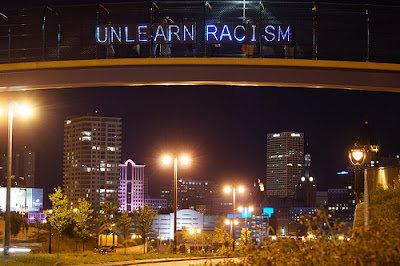

Thousands have marched, hundreds of thousands have signed petitions, millions have expressed their frustration, grief and outrage at the acquittal of George Zimmerman for killing 17-year-old Trayvon Martin in Sanford, Florida, last year. From New York to Los Angeles, protesters flooded the streets on July 14, chants of “No justice, no peace!” ringing through the night.

“No justice” is what many see as the outcome of a trial that would not even have occurred had authorities not been shamed by a similar public outcry into charging Zimmerman. Trayvon Martin’s death struck a nerve for reasons that went far beyond its immediate circumstances, and the not-guilty verdict reaffirms the sense that the whole justice system—from police to prisons—not only fails to protect people of color, but classifies them as criminals by default, even when they are the victims of a violent crime.

Monday, 29 July 2013

(No) justice for Trayvon Martin

Friday, 26 July 2013

Democracy and the eurozone crisis: quotes #16

The evidence presented in this report shows that the policy of prioritising austerity is not working and an alternative is required. The approach of imposing austerity measures and structural reforms aimed at reducing government borrowing and the debt/GDP ratio within a short number of years is not working in economic terms. Simultaneously, it is putting the social cohesion of Europe and the very political legitimacy of the European Union at risk.

Fair solution to the debt-crisis must be found: the recent EU agreement to recapitalise Spanish banks without adding to sovereign debt (June 2012) recognises that making taxpayers responsible for the massive debts of their banks is unsustainable. Turning banking debt into sovereign debt must be recognised as unfair and unsustainable for all affected countries and a fairer burden-sharing approach adopted.

Despite rhetoric to the contrary there is currently a failure to integrate economic and social policies, and a lack of a longer-term commitment to an inclusive society, which in turn is necessary to building a sustainable economy. The people paying the highest price currently are those who had no part in the decisions that led to the crisis, and the countries worst affected are amongst those with the biggest gaps in their social protection systems so their welfare systems are least able to protect their vulnerable populations. This process is unfair and unjust.

The above text is an excerpt from The Impact of the European Crisis, a report prepared by the Catholic organization Caritas Europa for Social Justice Ireland (2013, p. 5, original emphasis omitted).

Tuesday, 23 July 2013

Only love can be as perfect as that

Many musicians share their lives with cats, but I suppose few can sing to them as exquisitely as Patti Smith does in the following video; this is an excerpt from Steven Sebring's documentary film Patti Smith: Dream of Life.

Friday, 19 July 2013

So Close No Matter How Far...

Thursday, 18 July 2013

Democracy and the eurozone crisis: quotes #15

Photograph: Susana Vera/Reuters [elmundo.es]

The financial crisis and austerity measures in many EU countries have affected various economic and social rights, including those ensuring access to social security, housing, health, education and food. The measures often disproportionately affect the poorest and most marginalised people. Amnesty International believes that the EU, by signing and ratifying the Protocol [for the International Covenant of Economic Social & Cultural Rights], would demonstrate the 27 governments’ commitment to impose measures which respect human rights. It would also allow international accountability once all domestic avenues have been exhausted.Amnesty International is concerned that the EU-level debate on the financial crisis has yet to consider the human rights impact of austerity measures. It seems this aspect has been entirely absent from the discussion, despite the existing obligation to ensure that everybody can enjoy economic, social and cultural rights without discrimination. This obligation means governments must continue to protect human rights during a recession, particularly as vulnerable communities may be especially at risk.

Governments might argue that austerity measures, like public spending cuts, are necessary, but Amnesty International stresses their obligation to balance this with protection for human rights. It is an international obligation to ensure that measures are non-discriminatory, do not disproportionately undermine existing rights, do not hit the most vulnerable and disadvantaged people hardest and do not drive them further into poverty. International law also stipulates that measures must ensure minimum essential levels to guarantee each right, for example nobody should be left homeless, denied access to essential medical care, left hungry or become destitute.

Monday, 15 July 2013

Friday, 12 July 2013

Our power is in our principles

Poster: Brooke McGowen [occuprint.org]

Our power is in our principles. The power of Occupy has always been that it is an experiment in human freedom. That's what inspired so many to join us. That's what terrified the banks and politicians, who scrambled to do everything in their power—infiltration, disruption, propaganda, terror, violence—to be able to tell the word we'd failed, that they had proved a genuinely free society is impossible, that it would necessarily collapse into chaos, squalor, antagonism, violence, and dysfunction. We cannot allow them such a victory. The only way to fight back is to renew our absolute commitment to those principles. We will never compromise on equality and freedom. We will always base our relations to each other on those principles.

Wednesday, 10 July 2013

What is and what might have been

Sunday, 7 July 2013

Illegal and unconstitutional detention in Greece

Thursday 4 July marks one calendar month since Kostas Sakkas – a 29-year-old anarchist arrested in Athens in December 2010 and held in prison without a trial since – started a hunger strike, demanding an end to his detention. According to Greek law, pre-trial detentions can extend to 18 months, or 30 in exceptional circumstances. On 4 June, having already reached his legal maximum time in pre-trial detention, Sakkas had it extended by another six months by an Athens court of appeal.[...]Sakkas's case encapsulates precisely the nature of the injustice that reigns over daily life in Greece – and further afield. Across Europe, stories of police violence, governmental injustice and intrusion into citizens' lives are rapidly turning into a banality; an alienation, even an outright rupture between state and society is building up fast. In our fast-moving times, a month feels like a lifetime. For Sakkas, it has become precisely that: he has now put his own life on the line.

Online petition:

Tuesday, 2 July 2013

Spatial structure, fragmentation and subversion

Based on a Grid, 2012, Photograph: Kristof Vrancken [estherstocker.net]

The installation Based on a Grid is one of my favourite works by Esther Stocker; it was commissioned by the Z33 House for Contemporary Art for its 2012 exhibition Mind the System, Find the Gap in the city of Hasselt in Belgium. The aim of this exhibition was to criticise the political, economic, cultural, and spatial systems that govern modern society, and at the same time to locate and examine their gaps, leaks and ambiguities.

Based on a Grid is paradigmatic of the abstract and minimalist aesthetics of Esther Stocker's work, as well as illustrates the way in which its artistic choices inform and sharpen its politics. A grid is indeed provided: a holistic and internally complex geometrical system expands over the whole of the exhibition space and encompasses the potential viewers. At the same time, however, Esther Stocker breaks it down; although the space remains structured, most of the grid's segments and joints are missing.

The fragmentation of the grid is a critical act of empowerment, both symbolically and practically; it manifests that the spatial structure is not an all too powerful system, and it also enables mobility in ways which in effect defy the grid, and would have otherwise been impossible. And in this respect, Esther Stocker's work constitutes a challenge to the viewer by putting forward the issue of perception; one may choose to see order by visually connecting the missing links, but they may also focus on ruptures and openings that deconstruct the preceding perception of form and structure. The installation thus suggests a set of choices which are inherently political; and most importantly, it does so by posing a question and calling for an answer, rather than offering one. This may actually be seen as its most empowering aspect; and it is also a feature that runs through Esther Stocker's wider body of work.

O.T., 2006 Photograph: Rainer Iglar [estherstocker.net]

La solitudine dell'opera (Blanchot) Pt. 2, 2010 Photograph: Loredana Ginocchio [estherstocker.net]

Esther Stocker's installations are evocative spaces of potential freedom; through their abstract aesthetics, they seem to suggest that there is nothing objective or neutral about any form of spatial order, be that of a house or a prison, a factory or a university, a military camp or a museum. The works are conceptually dialogical and therefore open to interpretation; the production of meaning is located in the actual viewing process, which is substantially interactive and participatory.

To the extent that the installations are experienced in physical terms, perception and movement appear to be inseparable components of the viewing process; as Rainer Fuchs argues in an article titled Systematically Broken Systems, the works invite and enable interpretation through mobility:

For while grid paintings open onto feigned spaces, Stocker’s installations create spatialized images into which viewers can physically enter. In the MUMOK installation, with its white bar forms set at equal intervals into the black surfaces of the floor, walls, and ceiling, viewers find themselves in the midst of a clearly structured picture space, one which seems to have found in the bars — which essentially frame an empty center — a spatialized picture frame. The visual appearance of this self-framing space is perpetually transformed by the viewer's own movements and changing angles of vision. That seeing is not merely a physiological process of navigation, but instead a mode of dynamic interpretive behavior is adopted here as the point of departure for an art which signals mobility and displacement as the most concise, conceivable form of determination.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)