Although in the field of classical music it is symphonies that often get the lion’s share of attention, I was always more inclined towards piano concertos and sonatas; such as this sonata by Sergei Rachmaninoff. It is not because this particular gentleman moves me more than any other composer, but because he never seizes to surprise me. In this case he is addressing death, and he does so through the lens of a love for life that I have never come across before. And it is especially in the second part of this sonata that I have found myself returning in times of sorrow, as well as in times of joy. The following version is by Hélène Grimaud, one of the best contemporary pianists who has also not seized to surprise me. Listen to this piece particularly if you are not on the best terms with classical music – as with all things important, conventions are unnecessary, to say the least.

Friday, 30 March 2012

Piano sonata no.2 op. 36, by Sergei Rachmaninoff

Sunday, 25 March 2012

On the Road, with Jack Kerouac and Walter Salles

They danced down the streets like dingledodies, and I shambled after as I’ve been doing all my life after people who interest me, because the only people for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones that never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars and in the middle you see the blue centerlight pop and everybody goes “Awww!”

This is a characteristic excerpt from Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, one of the best novels of all time; reading this book is one of the most moving experiences I have ever had in any field of art. Intelligently multilayered and sweepingly improvisational, existential as much as subversive, aesthetically forceful and yet emotionally delicate, On the Road is the defining moment of the Beat movement, and a timeless manifestation of non-conformism.

It is far less known, however, that Jack Kerouac also envisioned a film based on the novel, which has now been made by the award-winning director Walter Salles. Similarly to the way he had followed the steps of the young Ernesto Guevara in South America in order to film The Motorcycle Diaries, Walter Salles prepared himself by tracing Jack Kerouac’s journey, interviewing Beat writers, and making a documentary titled In Search for On the Road.

The Motorcycle Diaries, Central Station, and Foreign Land, which was co-directed with Daniela Thomas, are examples of Walter Salles’ exquisite eye for road movies. As he told Michael Ordoña in the San Francisco Chronicle, “[w]hat truly interests me are stories in which the main characters’ journeys somehow mirror the transformations at play in a specific culture or country.” And in this respect, On the Road is a film I am most certainly looking forward to; the characters of Sal Paradise and Dean Moriarty, who in the novel stood for Jack Kerouac and Neil Cassady, are played by Sam Riley and Garrett Hedlund, while the supporting cast includes Kristen Stewart, Kirsten Dunst, and Viggo Mortensen.

Thursday, 22 March 2012

Moebius and Jimi Hendrix

One of the most impressive, and yet lesser known, aspects of Moebius’ work is his series of images of Jimi Hendrix. Moebius created the gatefold cover of the 1975 French compilation Jimi Hendrix/1 Are You Experienced, Axis: Bold As Love, part of which was also used as the cover of the 1995 compilation Voodoo Soup, while in 1998 he produced a portfolio of remarkable images. It is not often that one artist pays homage to another in such an imaginative and original manner; but it is not surprising, if one takes under consideration that it is precisely these qualities that characterised their groundbreaking work. And in this respect, it is only appropriate to refer to If 6 Was 9, perhaps the best track of the pivotal album Axis: Bold As Love by The Jimi Hendrix Experience.

If the sun refused to shine

I don’t mind, I don’t mind

If the mountains fell in the sea

Let it be, it ain’t me

Got my own world to live through

And I ain’t gonna copy you

Now if six turned out to be nine

I don’t mind, I don’t mind

If all the hippies cut off all their hair

I don’t care, I don’t care

Dig, ’cause I've got my own world to live through

And I ain’t gonna copy you

White collar conservative flashing down the street

Pointing their plastic finger at me

They’re hoping soon my kind will drop and die

But I’m gonna wave my freak flag high, high

Wave on, wave on

Fall mountains, just don’t fall on me

Go on mister business man, you can’t dress like me

Nobody know what I’m talking about

I’ve got my own life to live

I’m the one that’s gonna die when it’s time for me to die

So let me live my life the way I want to

Sing on brother, play on drummer

Sunday, 18 March 2012

In Time: survival of the richest – or, the politics of darwinian capitalism

In Time is written and directed by Andrew Nicoll on the basis of a particularly original idea. Imagine a future society in which time is the only currency; genetics has enabled people to stop aging at twenty-five, and from then on they can practically live for ever, as long as they earn time. Everyone has a counter on their arm; it may display hundreds of years, if they are rich, or just a few hours, if they are poor. The latter thus need to work so as to literally make a living, that is they depend on their daily wages to make it to the next day. The first half hour of In Time explores the workings of this dystopian society; at the end of each working day, for instance, labourers are credited with time, instead of money, which they use in order to pay for commodities as common as a cup of tea, or a bus ticket.

But in the context of In Time, the working class is dying out, and quite often in the crudest of ways. As the character of the rich Henry Hamilton (Matt Bomer) puts it, “for few to be immortal, many must die.” In this society the costs of production of labour consist of fragments of life, in the form of time. Labourers are thus engaged in a race against the clock, the cost of which is their very own physical survival; the value of their labour power is identical to that of their life.

In Time focuses on a factory worker named Will Solis (Justin Timberlake), whose mother Rachel (Olivia Wilde) runs out of time on her way back from work. Bus fares have suddenly gone up, the credit on her arm is not enough to buy her a ticket, and she can hardly make it on time if she returns on foot; she makes a run for it, only to die seconds before Will can transfer some of his time to her. Will subsequently seeks revenge and leaves Dayton, the ghetto of the poor, for New Greenwich, a suburb of the rich. The film thus serves as a metaphor for a world of strikingly unequal distribution of wealth and power, and polarised class opposition. Unfortunately, it gradually gives up on these narrative premises in order to become a rather conventional action/adventure film.

Will is persecuted by a police force known as the Timekeepers, and in order to escape he abducts Sylvia (Amanda Seyfried), the daughter of the incredibly wealthy businessman Philippe Weis (Vincent Kartheiser). Will subsequently asks for a 1,000 years ransom, which he plans to give away to the poor. Sylvia eventually takes his side, and joins him in bank robberies, and the concomitant distribution of free time to the people of the ghetto. The film thus incorporates references to Robin Hood, Bonnie and Clyde, and the story of Patty Hearst. In addition, the leader of the Timekeepers Raymond León (Cillian Murphy) adds a touch of Les Misérables to the film, coming across as a sci-fi version of Javert.

For the most part, however, character development retreats in favour of car chases and action sequences. Will, for example, in his confrontation with the Timekeepers and later on with a gang, inexplicably emerges as a trained fighter, rather than an ordinary worker. The affair between him and Sylvia also develops far too quickly to feel natural, and comes across as thin and rushed. Not least of all, the film shares the overt individualism which characterises the action film genre, and I must say that having seen Andrew Nicoll’s similarly dystopian first film Gattaca, I expected much more. In Time is not bad, but it feels very much like a missed opportunity; had it developed its characters further, and relied more upon its original concept, in other words what the businessman Philippe Weis addresses as “darwinian capitalism,” we would probably be talking about a contemporary sci-fi classic.

For the most part, however, character development retreats in favour of car chases and action sequences. Will, for example, in his confrontation with the Timekeepers and later on with a gang, inexplicably emerges as a trained fighter, rather than an ordinary worker. The affair between him and Sylvia also develops far too quickly to feel natural, and comes across as thin and rushed. Not least of all, the film shares the overt individualism which characterises the action film genre, and I must say that having seen Andrew Nicoll’s similarly dystopian first film Gattaca, I expected much more. In Time is not bad, but it feels very much like a missed opportunity; had it developed its characters further, and relied more upon its original concept, in other words what the businessman Philippe Weis addresses as “darwinian capitalism,” we would probably be talking about a contemporary sci-fi classic.

Tuesday, 13 March 2012

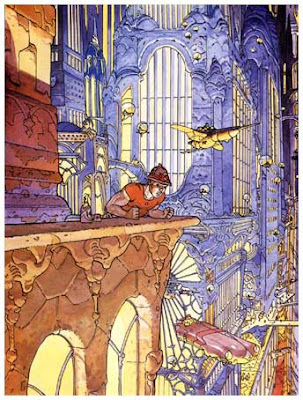

Jean Giraud/Moebius, 1938-2012

Jean Giraud, best known as Moebius, passed away on Saturday. He was an influential and internationally acclaimed comic book artist, illustrator, and designer; he was also admired by artists as diverse as Frederico Fellini, Hayao Miyazaki, Stan Lee, and Alejandro Jodorowsky. Jean Giraud began drawing and writing comics in France in the late 1950s, and his major breakthrough was Blueberry, which he drew under the pseudonym Gir. This series was created together with the writer Jean-Michel Charlier in the major European comics magazine Pilote in 1963. Blueberry was an unconventional and gritty take on the Western genre, and became an international critical and commercial success.

However, Jean Giraud felt confined within the parameters of the comics industry of his time, as did many other artists. His move towards the development of an innovative visual language in the art of comics was evident in The Deviation, a fantasy story which was published in Pilote in 1973. The next key development was the formation of the comics art group Les Humanoïdes Associés, of which he was a founding member, and the publication of Métal Hurlant in 1974; the group’s influential magazine was subsequently published in the US as Heavy Metal.

In Métal Hurlant, Jean Giraud worked under the pseudonym Moebius, and began to create fantasy/science fiction stories, such as Arzach, which were groundbreaking in terms of both the art of comics, and the development of the fantasy/science fiction genre. He subsequently collaborated with Alejandro Jodorowsky in the comic book series The Incal, which started in 1981, and with Stan Lee in the Silver Surfer: Parable miniseries, which was published in 1988/1989; he furthermore worked as a conceptual artist in major science fiction films. In his later career, Moebius drew and wrote the diary-like series Inside Moebius between 2000 and 2010; he also returned to the Blueberry series, and revisited his early fantasy work with the album Arzak: L’Arpenteur in 2010.

On Monday, the front page of Libération featured a portrait of Moebius by Enki Bilal, a prominent European comic book artist of the following generation, who began his career in Pilote, and subsequently published his science fiction stories in Métal Hurlant, and Heavy Metal. The portrait includes an image of the flying pterodactyl-like creature, a reference to Moebius’ trademark Arzach series. Moreover, the phrase “la bande décimée” paraphrases la bande dessinée, which is the French term for comics. Moebius’ death has indeed been devastating; but does it mean that this art form has now been decimated?

In order to address this question, one would have to take under consideration the wider social, political, and artistic context of Moebius’ era; and as in many occasions in the history of art, this was a time of radical change. Moves such as the formation of Les Humanoïdes Associés and the publication of Métal Hurlant in the mid-70s, were part of a wider aesthetic rift in European comics, which in France included magazines such as L’Écho des Savanes and (À Suivre), leading to the rise of auteur comic book art. As Moebius himself put it in the documentary Moebius Redoux: A Life in Pictures, in that era “society was freeing itself in an extraordinary way, and needed new talents to create something new, something that fitted the times.”

This new trend was thus of similar significance to what La Nouvelle Vague represented in the context of film. Furthermore, the new artists and publications revolutionalised the expressive means of their medium, and contributed to the wider acknowledgement of comics as an autonomous art form. Aesthetic innovation, however, cannot overshadow the fact that the new trends remained male-dominated, and that content was more often than not problematic in terms of its representation of gender, despite efforts such as the publication of the feminist magazine Ah! Nana.

In his key works in the 1970s, such as The Deviation, Moebius breaks down the composition of the page, and merges its contents by negating the use of conventional frames; moreover, in Azrach he develops unusual visual perspectives to put forward an entirely mute storyline. His clean and plastic line is instantly identifiable, and so is his taste for science fiction with a sense of irrationalism in the vein of the Theatre of the Absurd, delivered with a subliminal countercultural flair. It is thus hardly surprising that Moebius has been thought of as an innovator; and for the same reason, remembering him has also the value of a call for innovation itself: the next unpredictable step forward.

Additional information on Moebius:

Moebius on his art, fading eyesight, and legend: ‘I am like a unicorn’

Geoff Bucher, Los Angeles Times, 2011

Moebius Redoux: A Life in Pictures Part 1 Part 2 Part 3

BBC Documentary (Dir. Hasko Baumann, Avanti Media 2007)

Saturday, 10 March 2012

For my father, by Nuri Bilge Ceylan

Before the Rain, 2006 nuribilgeceylan.com

Award-winning director Nuri Bilge Ceylan happens to be a fine photographer as well. His latest project focuses on his father Mehmet Emin; both of his parents have actually taken part in many of his films. Especially in Clouds of May, my favourite Nuri Bilge Ceylan film, Mehmet Emin comes across as an engaging figure, evoking a harmonious relationship with nature, and an invaluable ability to find meaning in the simplest of things.

The photographs communicate a sense of inner peace and contemplation, and the slight melancholy that coming to terms with life occasionally involves. On the one hand, there are some very simple and common indoor activities at play; for instance, Mehmet Emin is making breakfast. And yet, he appears to do so in the most exquisite morning light, while the contrast between the angle from the darkened interior, and the focus on the source of light, evokes a sense of spirituality which is reminiscent of a religious space, rather than a kitchen.

The photographs communicate a sense of inner peace and contemplation, and the slight melancholy that coming to terms with life occasionally involves. On the one hand, there are some very simple and common indoor activities at play; for instance, Mehmet Emin is making breakfast. And yet, he appears to do so in the most exquisite morning light, while the contrast between the angle from the darkened interior, and the focus on the source of light, evokes a sense of spirituality which is reminiscent of a religious space, rather than a kitchen.

Mehmet Emin is furthermore placed in a natural environment, in long and medium shots which draw upon the light of the season. The former engage with the vastness of the landscape, while the latter address the details of the leaves, the soil, and the grass. In the long shots, the composition of the frame often signposts the human figure as a meeting point between the earth and the sky. Despite the overwhelming size of both, the delicate figure of Mehmet Emin is distinct not in opposition to the environment, but as an integral component of it; his presence appears to be as peaceful and natural as that of a tree.

The Road Home, Yenice, Çanakkale, 2006 nuribilgeceylan.com

Silent Meadow, Yenice, 2007 nuribilgeceylan.com

The medium shots allow a view of Mehmet Emin’s facial expressions and body language, and as a result, they display an immense contemplative quality which surpasses the content of the frame itself. To the extent that these pictures are medium shots of the human figure, they are also close-ups of the surrounding environment; and the focus on the former results in a deliberately limited and out-of-focus representation of the latter. And yet, Mehmet Emin’s gaze and posture emerge as subtle reflections upon all that cannot be fully or clearly seen, but can still be fully and clearly felt.

Backyard, 2007 nuribilgeceylan.com

Under the Oaks in his Field, 2007 nuribilgeceylan.com

Wednesday, 7 March 2012

Rethinking Whitney Houston

When Whitney Houston passed away, one could hardly find a website that didn’t state whatever views its writers had on the matter, or didn’t run some sort of retrospective of her career. Apparently, nothing attracts attention like a fallen star; and, unsurprisingly, not all of this attention was in the best taste. Inasmuch as I appreciated Whitney Houston, I felt that if this post was published at that time, it would be as if the blog was jumping on the bandwagon; and thus I decided to hold it back for a while.

Not least of all because it also seems that nothing sells like a fallen star. And thus Whitney Houston has posthumously become the first woman to have three albums in the top 10 of the Billboard chart at the same time. Nevertheless, what speaks louder than words about the workings of the music industry is the price increase of her greatest hits album on Apple’s iTunes store hours after her death, a move which Sony Music eventually took back and apologised for.

However, Whitney Houston was far more than a product. Her unprecedented popularity as a female African American artist in the field of music, and partly in film, signified what Bim Adewunmi addresses in The Guardian as “a huge cultural shift.” And it seems to me that this is a far more insighfull way to look at Whitney Houston than the conventional portrayal of a successful albeit troubled individual, which unfortunately prevailed in most mainstream media accounts.

Many thought of Whitney Houston just as a pop star, as her material was more often than not overtly polished. However, in the long history of jazz and soul music there have been many female African American singers who were heavily marketed in their time by a white-dominated music industry targeting a mainly white middle class audience. We think of such singers today as classic performers, and rightly so: the quality of their art surpassed whatever conventions were laid before them in their era.

Time will of course tell how Whitney Houston will be remembered. What I found fascinating about her was that her authoritative technique and the natural strength of her voice embodied the expressive quality of the gospels and the energy of soul; and I think it is this distinct cultural identity of hers that characterised songs like Saving All My Love For You, So Emotional, or I Will Always Love You. Whitney Houston actually moved into the gospel territory in The Preacher’s Wife soundtrack, with remarkable results such as I Love the Lord and Joy, while an often overlooked aspect of her work consists of songs dealing with pain and hardship, such as Step By Step and I Didn’t Know My Own Strength.

Dianne Reeves, perhaps the best jazz singer of our time, addressed Whitney Houston’s cover of Home as “flawless”; the track was performed during her first appearance on television, back in 1983. And speaking of days of old, Whitney Houston’s recording debut as a lead vocalist was on a cover of Memories by Material; a wonderful track featuring jazz legend Archie Shepp on saxophone. I have also chosen her powerful performance in The Nelson Mandela 70th Birthday Tribute concert in 1988, a political event calling for his release from prison. And last but not least, Your Love Is My Love; a track which seems to me as an appropriate way to say goodbye.

Clap your hands ya’ll, it’s alright

If tomorrow is judgement day (sing mommy)

And I’m standing on the front line

And the Lord ask me what I did with my life

I will say I spent it with you

If I wake up in World War 3

I see destruction and poverty

And I feel like I want to go home

It’s okay if you’re coming with me

If tomorrow is judgement day (sing mommy)

And I’m standing on the front line

And the Lord ask me what I did with my life

I will say I spent it with you

If I wake up in World War 3

I see destruction and poverty

And I feel like I want to go home

It’s okay if you’re coming with me

’Cause your love is my love

and my love is your love

It would take an eternity to break us

And the chains of Amistad couldn’t hold us

If I lose my fame and fortune

And I’m homeless on the street

And I’m sleepin’ in Grand Central Station

It’s okay if you’re sleeping with me

As the years they pass us by

we stay young through each other’s eyes

And no matter how old we get

It’s okay as long as I got you babe

’Cause your love is my love

and my love is your love

It would take an eternity to break us

And the chains of Amistad couldn’t hold us

If I should die this very day

Don’t cry, cause on earth we wasn’t meant to stay

And no matter what the people say

I’ll be waiting for you after judgement day

’Cause your love is my love

and my love is your love

It would take an eternity to break us

And the chains of Amistad couldn’t hold us

Sunday, 4 March 2012

The last precious thing she owns

Lee Jeffries tweeted this picture yesterday, and the title of this post is a phrase included in his tweet. It seems to me that it may as well be his best work; it certainly is the one I like the most.

Saturday, 3 March 2012

A rainy day unlike any other

Have you ever met a taxi driver who writes poetry? Or a poet who drives a taxi for a living? Obviously not, because there aren’t any, right?

Well, it was raining that day. I was on my way to work in the centre of Athens, and I had to be there by 14.30. I go there by train, and then change for the bus; when I went to the bus stop the rain was pouring, and there were delays because of the increased traffic. As the time was already 14.20, my only alternative was to stop a taxi. This is something I rarely do, but as I was fairly close to my destination it would only be a short and inexpensive ride.

Well, it was raining that day. I was on my way to work in the centre of Athens, and I had to be there by 14.30. I go there by train, and then change for the bus; when I went to the bus stop the rain was pouring, and there were delays because of the increased traffic. As the time was already 14.20, my only alternative was to stop a taxi. This is something I rarely do, but as I was fairly close to my destination it would only be a short and inexpensive ride.

I was sitting in the back seat going through my lecture notes one last time, when the taxi driver, a middle-aged working class man, asked for my opinion on the economic crisis. A year has passed since then and when I look back I realise that this was the most interesting discussion I’ve ever had on the matter. We were both so absorbed in it that we almost passed the point I was supposed to get off.

And as I was getting off, the driver suddenly asked me if I read poetry. It wasn’t exactly a question though; it sounded more like a statement of his impression of me, waiting for verification.

And as I was getting off, the driver suddenly asked me if I read poetry. It wasn’t exactly a question though; it sounded more like a statement of his impression of me, waiting for verification.

I said yes. And then he offered me a copy of his collection of poems as a present. Apparently he is a self-published poet, and a rather good one I must say. I wish I had a way to contact him and ask him if he would like me to post some of his work online. I can only hope that I will do so next time I run late on a rainy day; maybe this is the very beauty of such unexpected occasions. But still, there is something I think he would enjoy – it is the concluding part of Hollow Men, by T. S. Eliot:

Here we go round the prickly pearPrickly pear prickly pearHere we go round the prickly pearAt five o’clock in the morning.

Between the ideaAnd the realityBetween the motionAnd the actFalls the ShadowFor Thine is the Kingdom

Between the conceptionAnd the creationBetween the emotionAnd the responseFalls the ShadowLife is very long

Between the desireAnd the spasmBetween the potencyAnd the existenceBetween the essenceAnd the descentFalls the ShadowFor Thine is the Kingdom

For Thine isLife isFor Thine is the

This is the way the world endsThis is the way the world endsThis is the way the world endsNot with a bang but a whimper.

P.S.

And speaking of bangs and whimpers, the following links may be of interest:

After all, it was Thomas Jefferson who wrote that “banking establishments are more dangerous than standing armies,” in his letter to John Taylor, 28 May 1816, available at the Library of Congress. And if one was to put what the crisis is about in a nutshell, this phrase seems to me as a fine choice of words.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)